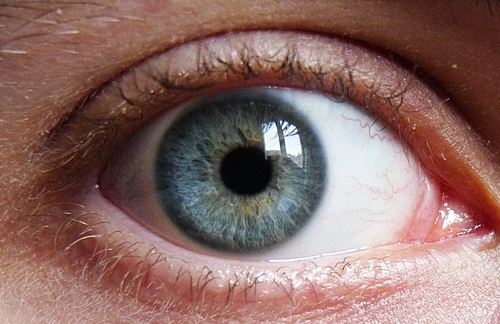

Our desires drive our perceptions.

Depending on what we *want*, our worlds will look wildly different.

Part of this is due to our attention. When we have a goal in mind, our attentional system becomes particularly attuned to related stimuli in our environment. When you’re on the lookout for that lost pair of keys in your house, you’re quick to notice anything that looks vaguely key-like (and you’ll likely find your keys much sooner than you otherwise would). So we literally see different things in the world depending on our aims. The best example of this is the “Invisible Gorilla” attentional blindness studies.

But part of this is also due to what’s called the “desirability bias”. This refers to our tendency to incorporate evidence that confirms our desires, and to throw out evidence that doesn’t.

In other words, we don’t incorporate the information that confirms what we already believe, we incorporate the information that confirms what we *want* to believe. These are usually the same thing, but they can differ…

According to this New York Times article, researchers from Royal Holloway, University of London were able to separate out the impact of the confirmation and desirability biases by looking at the reactions of voters to new polling information during the 2016 election.

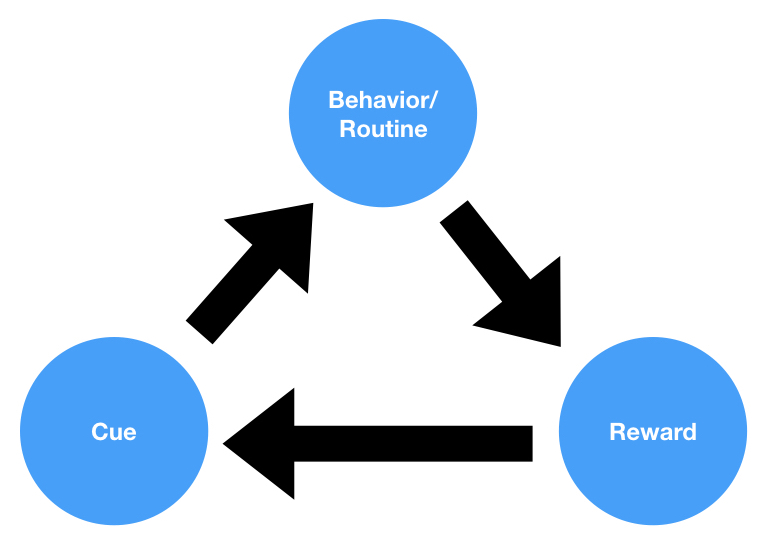

You had four groups of voters during the general election:

- Those who thought Hillary would win, but WANTED Trump to win

- Those who thought Hillary would win, and WANTED Hillary to win

- Those who thought Trump would win, and WANTED Trump to win

- Those who thought Trump would win, but WANTED Hillary to win

Thus, the experimenters had 4 groups of people, half of whom thought that their *desired* candidate was less likely to win. This allowed the researchers to separate out the impact of confirmatory vs. desired information.

Here’s what the researchers found:

“Those people who received desirable evidence — polls suggesting that their preferred candidate was going to win — took note and incorporated the information into their subsequent belief about which candidate was most likely to win the election. In contrast, those people who received undesirable evidence barely changed their belief about which candidate was most likely to win.

Importantly, this bias in favor of the desirable evidence emerged irrespective of whether the polls confirmed or disconfirmed peoples’ prior belief about which candidate would win. In other words, we observed a general bias toward the desirable evidence.

What about confirmation bias? To our surprise, those people who received confirming evidence — polls supporting their prior belief about which candidate was most likely to win — showed no bias in favor of this information. They tended to incorporate this evidence into their subsequent belief to the same extent as those people who had their prior belief disconfirmed. In other words, we observed little to no bias toward the confirming evidence.”

Over the last few months, confirmation bias has been all the rage. People like Scott Adamshave used it to describe almost everything we see in the political arena. But this research shows that it’s probably not confirmation bias that’s driving all the polarization… it’s desirability bias–which means that our strategy has to shift. We have to stop trying to show people that what they believe is wrong–we have to show people that they should desire something else. We have to paint a juicy, shiny picture of what we want them to desire, and hope that they find it enticing enough to make the switch.