Back in 2012 I was worried. Really worried.

I felt that, like Tony Stark in The Avengers, I had come across some secret power that, in the wrong hands, could cause great destruction.

While I was mainly working on self-improvement and wellness products, I thought that I might be on the verge of opening Pandora’s box.

“Behavior Design” was just getting popular, and I was one of the people at the forefront of the movement. We were getting quite good at creating fun, easy-to-use, habit-forming apps. What if those with improper aims grasped this power? What if gaming companies could get people to use their apps for so long they would later need reconstructive thumb-joint surgery? What if e-commerce titans could get people to purchase books until they defaulted on their mortgages and sold off their pet cats to support the habit?

In a moment of guilt, I wrote an article for GigaOm called “When Did Addiction Become a Good Thing?”. You can read it here.

However, over the years, I’ve become more and more skeptical that digital addiction is a true addiction. Part of this is due to my neuroscience background. In many of my college courses, we studied the neurobiology of addiction. The dramatic biochemical and neuroanatomical changes there seemed like they would require quite robust biochemical insults–from drugs/chemicals instead of Pokemon or Instagram.

In support of this point of view, the New York Times recently published a fascinating article. Here are a couple of key passages from the piece:

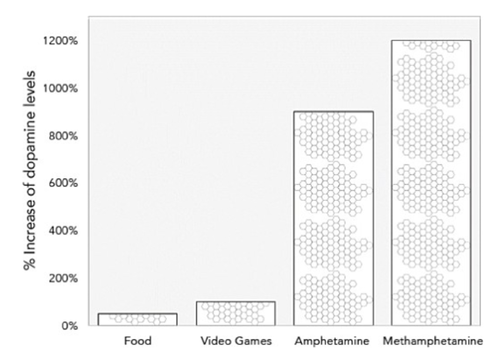

Let’s start with the neuroscientific analogy: that the areas in the brain associated with the pleasures of drug use are the same as those associated with the pleasures of playing video games. This is true but not illuminating. These areas of the brain — those that produce and respond to the neurotransmitter dopamine — are involved in just about any pleasurable activity: having sex, enjoying a nice conversation, eating good food, reading a book, using methamphetamines.

The amount of dopamine involved in these activities, however, differs widely. Playing a video game or watching an amusing video on the internet causes roughly about as much dopamine to be released in your brain as eating a slice of pizza. By contrast, using a drug like methamphetamine can cause a level of dopamine release 10 times that or more. On its own, the fact that a pleasurable activity involves dopamine release tells us nothing else about it.

A large-scale study of internet-based games recently published in the American Journal of Psychiatry bears out our skepticism about this “addiction.” Using the American Psychiatric Association’s own metrics for ascertaining psychiatric disorder, the study’s researchers found that at most 1 percent of video game players might exhibit characteristics of an addiction and that the games were significantly less addictive than, say, gambling.

Which reminds me of a story…

True Addiction

It was about 5:15 in the morning and I was cold. My breath formed clouds in front of me as I scampered down the sidewalk, head down from the strain of my backpack.

Suddenly, in the dead quiet of the early morning, I felt a bony hand clutch my shoulder. A tingly, electric jolt shot through me. Adrenaline. I jumped back and looked up at the gaunt, sweatshirt-clad figure that loomed in front of me. There was just enough light for me to catch the structure of his face: a set of interlocking rectangles–all sharp angles. He was in bad shape; an emaciated homeless man.

And there I was, face to face with this figure, adrenaline coursing through my veins, ready to fight if necessary.

“Want some crack?”

His voice was froggy, high pitched.

He continued: “How much money you got? Five bucks?”

I tried to walk forward, but he was surprisingly fast. He blocked my path and lurched towards me.

Again: “I’ll take anything you got. Here — I’ve got crack. Five bucks.”

We were going to collide. I put my hands out in front of me and felt his sunken chest press into my hands. I pushed as hard as I could. He went back a few feet, tripping a little, startled.

This gave me enough space for me to make my move. I was off and running down the street to my apartment — safe.

Over the coming weeks, I walked by the street-corner dozens of times. Each time I would be on the lookout for that terrifying, but sad, man. He was never there. I assumed that he either moved on to a new spot or passed away. He was, after all, in quite terrible shape.

About 5 years later, long after I had moved out of that area (The Mission), I found myself in the subway station near that same street corner. I was poking my hands around in my pockets, looking for my wallet, so that I could purchase a ticket.

While doing this, a beggar came up to me and asked for some change. “Sorry, I’ve got no cash.” He thanked me and started to turn, which is when I saw his face.

It was the same man, but he looked different.

Most of his teeth were missing, and he was hunched over. His shoulders curled in towards his chest. And he seemed… shorter. It was as if he had been left in the dryer too long. All of his features were sucked in, shrunken.

We made eye contact for a second or two and then he walked off. I haven’t seen him since.

A lot of people think that smartphones are these addiction engines, perfectly designed to “hook” their users; ensnaring them in endless time-wasting activities. While I don’t deny that smartphones and their associated apps are quite engaging (and can consume a lot of time and attention), I do take issue with them being characterized as “addictive”… and I don’t think that the smartphone-checking/using behavior is, itself, the problem, anyways.

In this section, I want to make the point that smartphone/tech addiction isn’t a real addiction, and to call it one is hyperbolic and irresponsible.

Have you ever heard of someone being so addicted to a video game (or Facebook) that they weren’t able to hold a job and earn a living? Have you ever heard of someone scrolling through their Twitter feed so much that they ended up on the street, unable to escape the ravages of homelessness? Me neither.

Addiction is a serious thing. It’s heartbreaking. It’s bloody. It destroys lives and families. It decays the body, the mind, and the spirit of the person in its clutches.

So, when we call something an addiction, we better be sure it’s worthy of the label.

In the case of “smartphone addiction” and “technology/app addiction”, this is not the case. Having trouble controlling your desire to see what your friend Michael is up to, or getting caught up in a 30-minute nostalgia session, is on a completely different, less serious level.

You may think that everything I’ve said up to this point sounds nice, but is there *really* any scientific evidence for what I’m saying? Yes. From a neurobiological point of view, we can actually quantify how addictive something is likely to be. How can we do this? By measuring dopamine levels in the brain. When you’re getting fully stimulated by tech (a video game, in this case), your dopamine levels actually double (compared to a baseline, resting state). Sounds huge, doesn’t it?

Well — that’s about the increase you’d get while eating a piece of pizza.

But it’s TINY compared to the increase that amphetamine or methamphetamine causes. Let’s, once again, look at the chart referenced by the authors in the New York Times piece quoted earlier:

Mmmm… dopamine…

It’s not even close.

Yes, smartphones and tech can be stimulating… but the most stimulating, engrossing form of consumer technology (a video game) is an order of magnitude less stimulating than an actually addictive drug.

So does that mean there’s no problem?

No.

It means that there may be even deeper, more pernicious issues at play.

The Problems Underneath It All

If you’re reading this article, you (like me) probably have a good life. Your biggest problems are probably things like figuring out which Netflix Original series you should watch this weekend, or whether to order takeout or stir-fry up some grass fed beef and kale for dinner.

I’m not saying this to be rude or point out how I’m different. I’m in the same exact boat as you.

I’m saying all of this to make a point — in the scope of human history, we have it pretty darn good. Our problems don’t consist of finding enough food or surviving through the winter. And those of us on this list are (probably) in the enviable position of not having to live from paycheck to paycheck. We’re high on the hog, so to speak.

But that doesn’t mean our lives are perfect. Certain parts of our existence have gotten worse. Our community lives aren’t as strong as they used to be. Civic trust and engagement are at an all-time low.

In other words, the social aspects of our lives are in a precarious position.

In addition, by moving on from some of the lower level problems of life (surviving, eating, etc.), we’re now faced with some of the hairy, high-level concerns of existence: am I living up to my purpose? Have I found true love? and so on.

And these concerns are stressful. Really stressful. This is, in part, due to the fact that they’re so nebulous. They’re fuzzy, unformed. We don’t feel like we’re living our purpose on some deep level, and so we have this feeling of unease we can’t quite put a finger on. Or we constantly feel a little anxious and stressed, but we can’t make the connection between this and something like the lack of community where we live. After all, it’s hard to see a negative — the absence of something.

But that doesn’t mean we won’t come up with some explanation, no matter how wrong it may be, for what we’re feeling and going through. We humans are master explainers, master storytellers. We come up with causal explanations for everything. It’s just what we do.

And so we look around our environment for the cause of this anxiety that plagues us… and what do you think stands out?

First, things that are new. They stand out.

Second, THINGS pop out — not the lack of things.

Third, things that are dynamic, ever-changing. Movement draws and keeps our attention.

Can you think of anything that fits those three criteria?

Technology.

Tech is what’s new–shiny.

It’s flashy and easy to see. It doesn’t really meld into the background.

And it’s ever evolving and changing. It’s rare that some piece of technology is installed in our environment and just sits there for decades, untouched. Just walk into any office in America–the computers are changed at least once every 2 years (often more frequently).

For these reasons, tech is almost always top of mind, and it’s easy to point a blaming finger at.

This has happened before (think Luddites), and it will happen again. But just because something is fashionable doesn’t mean that it’s true.

Which leads to my next question: Do you fidget?

Do you ever bite your nails?

When you’re stressed do you like to just get some running shoes on and just sprint as long and as hard as possible?

All of us have stress coping mechanisms — things we do to feel better about our situation. Some people crack their knuckles, some people smoke. Others eat. Others play video games.

If you’re really, really stressed do you think you’ll do these things more or less?

More, obviously.

So, let’s say that due to the degradation of civic engagement and community trust and bad diet, etc. you just feel… bad. Uneasy. Anxious. But you don’t really know why. You start playing a game that makes you feel better. It’s a small part of your life where you have some degree of control, and you connect with really cool people while you’re playing it. You guys start to log into the game every day and hang out. The game gives you a clear sense of progress. You’re leveling up, getting better, and becoming the leader of your online tribe.Your friends and family start to get worried. They see that you’re kind of nervous and, from what they can see, you’re spending an awfully large amount of time playing that game… They think you’re addicted, and that your “game addiction” is causing the anxiety.

But, from the picture I painted, do you think that’s really the case?

This, in my mind, is a clear case of correlation being mistaken for causation.

Your game play increases with your stress, but it’s not the cause of it. In fact, it’s an attempt by you to alleviate the discomfort you feel.

I think that we’re seeing the same thing with “tech addiction”. We naturally assume that X (tech) causes Y (stress) when some third factor (or many factors), Z, is actually the driving force behind Y.

Just look at the state of the world today. We have unprecedented political polarization, growing inequality, and automation (and crummy policies) causing the destruction of millions of jobs. It’s a stressful time to be alive, so it’s understandable that people will look for outlets and coping mechanisms. We might even engage in behaviors that some consider “addictive” or inappropriate, such as playing video games, scrolling through our social network news feeds, and logging many many hours in other online communities (like Reddit).**

Does that mean that these things are the problem? No, probably not. They’re coping mechanisms. If you take them away, people will just find other ways to let out that steam and gain a sense of control and comfort. Those things may be “better” and more productive, or they might be much worse (drugs, etc.). In fact, millennials are using fewer drugs than previous generations, but spending much more time on their smartphones:

But researchers are starting to ponder an intriguing question: Are teenagers using drugs less in part because they are constantly stimulated and entertained by their computers and phones?

The possibility is worth exploring, they say, because use of smartphones and tablets has exploded over the same period that drug use has declined. This correlation does not mean that one phenomenon is causing the other, but scientists say interactive media appears to play to similar impulses as drug experimentation, including sensation-seeking and the desire for independence.

Or it might be that gadgets simply absorb a lot of time that could be used for other pursuits, including partying.

So, I ask you: Do smartphones *really* seem like the problem? Are these “addictions” causing harm? Or are they merely stress relief mechanisms, improperly maligned due to sloppy thinking (correlation does not equal causation)?

You know how I feel. What do you think?

**We know that in times of stress people seek out social support, so you would expect social media use to rise in times of stress–both chronic and acute.