Table of Contents

Hooked: How To Build Habit Forming Products By Nir Eyal and Ryan Hoover

Over the years, I’ve gotten a lot of questions about habit formation and product design. People want to know if there’s good research on how to get people to build a habit around your product or service, and they almost always bring up the book Hooked: How To Build Habit-Forming Products by Nir Eyal and Ryan Hoover. While I believe that the book has a great title and is well marketed, I don’t think it presents readers with an effective, research-backed overview of the topic.

In fact, it is my belief that it will harm the product design efforts of anyone who tries to follow its advice.

I wrote an article outlining my initial criticisms back in 2014. You can read it at Bigthink or on my website.

Below I’m going to review the book’s main points and my criticisms. Then I’m going to provide you with a model of habit formation that I believe is more practical, research backed, and effective.

Why Should You Listen To Me?

- I helped create the field of Behavior Design at Stanford with Dr. BJ Fogg

- I created the first Behavioral Science unit at a Fortune 100 company

- I was Global Head of Behavioral Science at Walmart

- I created the first applied behavioral science firm in Silicon Valley

- I’ve worked with dozens of companies on product design and behavior-change projects

- I studied neuroscience at Stanford, and have been an applied behavioral scientist for almost 14 years

- I’ve created two successful behavioral science based companies, Kite.io and Persona

Summary Of Hooked: How To Build Habit-Forming Products

The book focuses on laying out a model of habit formation and illustrating how it can be applied to product design.

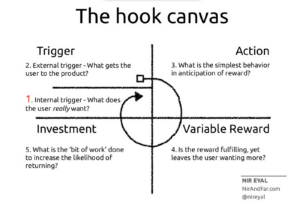

Here’s the model, taken from the author’s website:

The Hooked Model breaks habit formation into four neverending steps:

- Trigger

- Action

- Variable Reward

- Investment

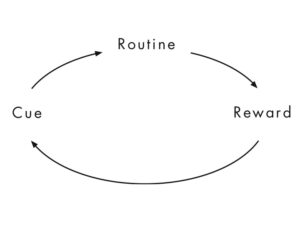

This model is a slightly revised version of Charles Duhigg’s Habit Loop, which he covered in his 2012 book, The Power of Habit:

As you can see, the main difference is that Cue has been renamed Trigger (a term coined by Nir’s original Behavior Design teacher, BJ Fogg), Reward has been re-labeled Variable Reward, Routine has been relabeled Action, and an additional step, Investment, has been added. Two of these changes are cosmetic, while two of them are more substantive:

Cosmetic changes:

- Cue changed to Trigger

- Routine changed to Action

Substantive changes:

- Reward changed to Variable Reward

- Investment added as step

According to Nir, the path to building a habit-forming product is by having users go through the Hooked loop as many times as possible. The more they go through it, the stronger the habit gets.

Let’s lay aside the fact that this is circular logic (a person doing something repeatedly is the basic definition of a habit, so it’s not very useful to say that people form habits by doing something repeatedly).

However, that’s not where my main criticisms lie. My main issues are with the model’s additions:

- the addition of *variable* rewards

- the addition of an “Investment” step

In fact, both of these things invalidate the model and destroy its predictive capabilities.

Variable Rewards

The research on variable rewards dates back to the 1930s, when BF Skinner and members of the Behaviorist school of psychology were running experiments on reward schedules. They would put rats or pigeons in carefully constructed boxes called Skinner Boxes and look at how different reward patterns would impact their behavior.

They discovered that variable rewards were particularly good at preventing what they called “extinction”. This is when a behavior decreases in frequency and eventually stops being performed. This discovery was the beginning of the obsession with “Variable Rewards”.

Over the years, practitioners took research from the Behaviorists and used it for a variety of different purposes, but it mostly took off with animal trainers. In fact, it seems like animal training is where behaviorist ideas have had the most use and success.

Animal trainers realized pretty quickly the importance of variable rewards, but only *after* an animal had learned how to do a behavior via a continuous reward schedule.

For example, Karen Pryor, inventor of Clicker Training, gives the following advice:

“During shaping of a new behavior, each time you establish the behavior, the dog is being reinforced on a continuous schedule: that is, it does the behavior and it gets the click/treat. As soon as you want to improve the behavior, however, and you raise a criterion, the dog is on a less predictable schedule. The requirements are a little different and it will probably not get reinforced every time. From the dog’s standpoint, the schedule has become variable. When the dog is meeting the new criterion every time, the reinforcement becomes continuous again.”

In other words, to establish a new behavior you want to use continuous rewards. To improve the behavior, however, you should use variable rewards.

In her classic book, Don’t Shoot The Dog!, she talks about the importance of the continuous to variable shift:

“There is a popular misconception that if you start training a behavior by positive reinforcement, you will have to keep on using positive reinforcers for the rest of the subject’s natural life; if not, the behavior will disappear. This is untrue; constant reinforcement is needed just in the learning stages. You might praise a toddler repeatedly for using the toilet, but once the behavior has been learned, the matter takes care of itself. We give, or we should give, the beginner a lot of reinforcers—teaching a kid to ride a bicycle may involve a constant stream of “That’s right, steady now, you got it, good!”

“In order to maintain an already-learned behavior with some degree of reliability, it is not only not necessary to reinforce it every time; it is vital that you do not reinforce it on a regular basis but instead switch to using reinforcement only occasionally, and on a random or unpredictable basis.

This is what psychologists call a variable schedule of reinforcement. A variable schedule is far more effective in maintaining behavior than a constant, predictable schedule of reinforcement.”

So is the reward stage as simple as “Variable Reward”? No. As we can see, the optimal strategy is to use a mixture of different types of rewards. Not just variable, but continuous as well—especially in the beginning stages of habit formation.

If this is the case, then the best way to represent this stage of the habit formation process would be to call this stage “Reward”, since this would include both variable and continuous rewards. However, Nir’s model discounts the importance of continuous rewards, even though they’re just as important for habit formation as variable rewards.

In fact, you could argue that it would make more sense to label this step of the habit formation process “Continuous Reward”. Why? Because, in nature and in real life, Variable Rewards are the norm. Continuous Rewards are much less common and more unique to the digital world. They are a unique feature of our modern artificial environment, and allow for product creators to do something evolutionarily novel. David Myers, writer of the most popular Psychology textbook, states this well:

“Real life rarely provides continuous reinforcement. Salespeople do not make a sale with every pitch. But they persist because their efforts are occasionally rewarded. This persistence is typical with partial (intermittent) reinforcement schedules, in which responses are sometimes reinforced, sometimes not. Learning is slower to appear, but resistance to extinction is greater than with continuous reinforcement.”

Paul Chance, another well regarded learning psychologist, explains things similarly when he talks about variable ratio rewards, a type of variable reward:

“Variable ratio schedules are common in natural environments. As fast as the cheetah is, it does not bring down a victim every time it gives chase, nor can it depend on being successful on the second, third, or fourth try. There is no predicting which particular effort will be successful. The cheetah may succeed on two attempts, and then fail on the next ten tries. All that can be said is that, on average, one in every two of its hunting attempts will pay off (O’Brien, Wildt, & Bush, 1986). (For many predators, the ratio is much higher than that.)

Probably most predatory behavior is reinforced on VR schedules, although the exact schedule varies depending on many factors.”

So calling out variable rewards as something uniquely important to building digital habits seems a little strange. Variable rewards are the norm in the real world. But in an artificial environment we have the ability to engineer continuous rewards and quickly create a behavior → reward connection in participants.

Thus, Nir’s modification of Duhigg’s “Reward” step to “Variable Reward” seems like an attempt to make his model seem different, while also making it less accurate and useful.

Let’s review what we’ve covered so far:

- Continuous reward schedules are more effective than variable rewards at the beginning stages of the habit formation process

- Animal trainers start with continuous reward schedules and then move to variable schedules over time

- Variable reward schedules are the norm in nature and in the real world

- Continuous reward schedules are a novelty in the modern, artificially constructed world

- The superpower of digital products is their ability to deliver reliable continuous reward schedules

This leads us to the next issue with Nir’s insistence on Variable Rewards: they make for bad product design.

The entire purpose of Hooked is to help people create better products that are more likely to be used regularly.

Which product do you think people will come back to and use more frequently?

- The grocery delivery app that always has what you want in stock.

- The grocery delivery app that sometimes has what you want in stock.

The first one, right?

The consistency of the reward (getting the groceries you want) is much higher in the first option. It is using a continuous reward schedule.

The second option has a less reliable reward–it has a variable reward.

I’ve worked on dozens and dozens of products, and I can assure you that the second product will be much less retentive and habit forming than the first product. But this directly contradicts the assertion of the Hooked Model that variable rewards need to be used.

In fact, with almost every single type of product, continuous rewards are going to be better and more habit forming than variable rewards. Most products are utilities. They’re built to help people solve practical problems. With a utility, you don’t want any variability. You just want the product to solve your problem quickly and efficiently every single time. Variability of reward in the context of a utility is a death blow.

So if a product designer building a utility product took the Hooked Model seriously and added variability into their reward schedule, they would just end up building something terrible: a product that only sometimes solves a user’s problems.

I’ve spent a few hours thinking through the implications of this step of the Hooked Model the last few years, and, to be totally honest, I can’t think of any way it’s helpful or practical. In most cases, I’m not sure adding variability into a product would be useful or beneficial. Maybe you could add in some random jackpot awards, or throw in other surprises here and there? In some circumstances that could be compelling, but I’ve implemented changes like this in products and they generally have a lackluster effect. They may cause a short-term boost in activity, but the medium and long term impact on retention and engagement is close to zero. Changes like this have a much smaller impact on user experience and retention than good usability and a user experience focused on reliably solving a real problem.

I actually think that, by focusing on variable rewards, Nir got the opposite of the real lesson: technology allows us to, for the first time in history, create reliable continuous reward experiences. While our ancestors only sometimes captured a deer while out hunting, today we can get a steak delivered reliably whenever we want. Consistency is the magic of the digital world, and what allows us to create customers who are raving fans.

The Investment Step

Nir describes the Investment step as follows:

“The last phase of the Hook Model is where the user does a bit of work. The investment phase increases the odds that the user will make another pass through the hook cycle in the future. The investment occurs when the user puts something into the product of service such as time, data, effort, social capital, or money.

However, the investment phase isn’t about users opening up their wallets and moving on with their day. Rather, the investment implies an action that improves the service for the next go-around. Inviting friends, stating preferences, building virtual assets, and learning to use new features are all investments users make to improve their experience.”

In the first version of Nir’s Hooked Model, the Investment step was clearly last:

I believe that, based on the criticism I published on Big Think, he revised to model to make it an infinity sign with no clear beginning step:

This change was necessary because the old version of the Hooked Model was contradicted by nearly every billion-dollar app in existence.

Here’s what I mean: Almost every single successful app has you go through an onboarding experience the first time you use the product. For example, when I sign up for a Twitter account, I’m asked to do the following before I can Tweet:

- Tell them which topics I’m interested in

- Follow celebrity accounts

- Create a profile

- Sync my address book/contacts

The same thing is true of apps like Airbnb, Instacart, Amazon, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, Uber… you name it. Very few apps don’t require you to invest time and energy before your first usage, Google being the most notable example.

So we have a situation where nearly every digital product asks you to invest up front. This observation destroyed the validity of the structure of the first version of the Hooked model, and required its revision into its current form: an infinity symbol with no specific beginning.

But this revision doesn’t solve the problem, because after going through the onboarding process during your first experience, you are not *then* presented with a trigger to open and engage with the app.

So the Hooked Model doesn’t properly reflect what is, arguably, the most important part of the user experience of a product: the first-time user experience.

If you botch a first-time user experience, you probably aren’t going to get a second chance. During that first experience, you have to impress and delight the user. Or you, at least, have to present a solid case that you’re valuable enough for the user to allow you to send push notifications (and not delete you from their phone).

So we can see that the Hooked Model does not appropriately model the first-time user experience of most habit-forming apps in the market.

But it also misrepresents the true nature of user investment and how it contributes to a habit-forming user experience.

According to the Hooked Model, the Investment step is a discrete phase that comes after the Variable Reward step and before the Trigger step.

However, as we just covered, investment normally occurs up-front during the first-time user experience. And, once a user has joined an application, Investment is almost always a function of a user’s normal activity in the app. Let me give you a couple of examples:

- Amazon:

- Amazon does not ask me to give it a bunch of information about myself and spend time investing into the app after I’ve purchased something from them. The searches I did and the purchase I made *was* the Investment. They just got a good deal of data about me that they can then use to make my user experience better in the future and send me personalized emails (Triggers) etc.

- In the case of Amazon, Investment occurs *during* the Action phase. It is synonymous with the Action phase. The Action that I am taking in the app is my investment in the app.

- Netflix:

- Netflix doesn’t ask me to take a bunch of quizzes or tell it which movies I like when I normally use the application.

- Instead, it learns from what I watch and what I click on, and makes my recommendations and user experience better based on my normal app Actions.

- In other words: Investment is also synonymous with Action.

I would encourage you to analyze every product you can. You will be hard pressed to find a successful product that has Investment as a discrete, standalone step after Action and its corresponding reward. In almost every digital product, Action and Investment are the same thing.

What does this mean?

It means that we do not need Investment as a separate step of the habit formation process. Investment should merely be something that is noted about the Action/behavior phase of the habit formation process.

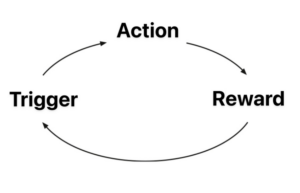

However, without the Investment step of the Hooked Model, we’re left with something that looks almost identical to Charles Duhigg’s Habit Loop (though with slightly different labels):

Can you spot the difference?

To summarize:

- In the first version of the Hooked Model, Investment came as the 4th step in the habit formation process.

- However, almost every popular app has users invest up front during a new user onboarding experience, which invalidates the Hooked Model for the first time user experience.

- In almost every digital product, users invest by doing the core actions in the app.

- I have been hard pressed to find a successful digital product that has users invest in some way that is separate from the app’s core action–as a discrete step that occurs after the reward.

- After the new user onboarding, Action and Investment are synonymous, making the Investment step in the Hooked Model unnecessary.

- With the Investment step deleted, and the validity of Variable Rewards called into question, the Hooked Model is almost indistinguishable from Charles Duhigg’s Habit Loop.

Concluding Remarks

So where does this leave us?

If we are to take what Nir has created and correct it to more accurately reflect the scientific literature and the world we see in front of us, we are left with a habit model that looks like this:

We are left with a re-labeled version of Charles Duhigg’s Habit Loop.

Which brings up the question: Is the Habit Loop useful? What does it teach us about habit formation that’s practical for product design purposes?

To be honest, almost nothing.

What product designer doesn’t think that they should reward their users with a desired outcome for doing things inside of their app?

What product designer doesn’t think they should send their users notifications or emails to try and get them to perform actions inside of their app?

The answer to both these is: none of them.

The Habit Loop does express that habit formation is an ever-repeating process. But that’s a bit of a tautology. Habits are, by definition, repetitious. So showing that a repeating activity repeats is a bit too circular to be meaningful.

Where does that leave us with the science of habit formation as it relates to product design?

There’s a lot of good, useful information from the behavioral sciences as to how people form habits and what the purpose of habit formation is. I talk about some of this research here and here.

If this analysis of Hooked has shown anything, though, it’s the unique and evolutionarily novel power of consistent rewards. With modern technology, we now have the ability to ensure that people are able to solve their problems consistently and easily. We can make sure that people are always able to get the groceries they want delivered on time (Instacart). We’re able to make sure that they can find that fun article they read three years ago (Google or Pocket). We’re able to make sure they can meet their friend across town for a drink in a timely fashion (Uber or Lyft). We’re able to let them find a hotel room for their last-minute weekend getaway (Kayak, Expedia, Google, Booking.com). We’re able to continuously shower them with good things.

Fortunately, we’re out of the primal world of uncertainty and variability, and into the world of technology.

Author’s Final Thoughts:

Hooked by Nir Eyal is not a good how to guide. Based on my analysis, I do not believe that the tactics covered will help product designers create user habits or reliably change customer behavior. The fact of the matter is that successful habit forming products are those that effectively, easily, and enjoyably solve a problem. They do not require investment or variable rewards. Building habits is something that our brains naturally do when they discover a solution to a recurring problem. Startup founders, product managers, and product designers should be focused on discovering real user pain points and coming up with reliable, easy, and enjoyable solutions for those problems. The more that they focus on distractions like internal triggers, external triggers, and reward variability, the worse their results will be. Successful companies create products based on tangible user needs not abstract theory.

Most habit forming companies were founded by people who were experts in either technology or a specific target market. I’m not aware of a single multi billion dollar company that was founded by someone with a background in psychology and behavioral science. This is because driving customer engagement (especially unprompted user engagement) is a function of practical insights, product ability, domain expertise, and deep empathy. Many successful companies (if not most) are filled with leaders who have barely thought about the human brain. This is not to say that behavioral science insights are not useful, but that they are only a small part of the picture.

Technologies hook users and modify user behavior not through clever tricks that subtly encourage customer behavior, but by providing genuine and real value. Clever tricks and their associated products capture widespread attention on social media and on sites like Medium, Harvard Business Review, etc. But it’s the basics, like an understandable UX and useful features, that count. However, no one ever bought a book that told them that building a product is hard and requires painstaking user research and dozens of rounds of iteration. That wouldn’t be sexy enough. Instead, people want to hear that there are powerful psychological tools companies can implement to “hook” people. Luckily, this isn’t the case. Luckily, the products that are the most artfully done and the most useful for real human needs are the ones that take off and win our time, attention, and hearts.

How Do You Create Habit Forming Products?

You choose the right behavior for your product. A habit forming product is built around The 4 Es:

- Effective

- Easy

- Enjoyable

- Exciting

If you can build a product that effectively solves a problem in a way that is easy, enjoyable, and exciting, then it’s quite likely your creation will be habit forming.

To learn more about this, you can search my blog for related articles. Here are a couple to get you started:

Further Resources And Courses

If you’re interested in building your own habit forming product, or helping other people get better at building habit forming products, please fill out this form to learn about my course on How to Build Habit Forming Products. I share the things I’ve learned over the last 13 years building habit-forming products. Why should you listen to me? I created the first applied behavioral science team at a Fortune 100 company, helped develop the field of Behavioral Design at Stanford with Dr. BJ Fogg, and have created a growing new discipline called Behavioral Strategy.

While the course is geared towards start up founders and those at technology companies, the lessons can be applied to any product or service in any industry.

To read more about the Hooked book, click here.