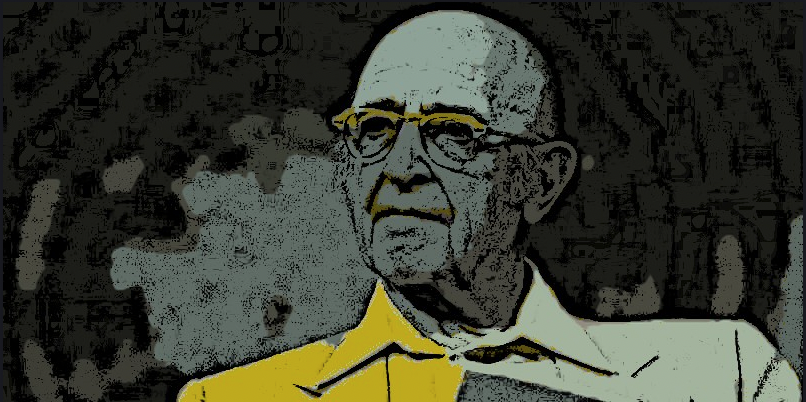

The following is a transcript of a talk Carl Rogers made in 1974 on the topic of empathy.

“Many years ago, I realized how powerful it was to listen to a person. In recent months, I’ve been working on a paper trying to take a fresh look at the power of listening, at the power of an empathic way of being, and that’s what I want to talk to you about.

We should reexamine and reevaluate that very special way of being with another person, which we call empathic. I believe we tend to give too little importance and consideration to an element which is extremely important in the understanding of personality dynamics, and for affecting changes in personality and in behavior. I think it’s one of the most delicate and potent tools that we have, and I’m impressed at how rarely we see it in real-life situations, in any full-fledged form.

I guess I’ll start with my somewhat faltering history in relation to this topic. Very early in my work as a therapist, I discovered that simply listening to my client very attentively was an important way of being helpful. When I was in doubt as to what I should do in some active way, I simply listened, and it seemed surprising to me that such a passive kind of interaction could be so useful.

A little later, a social worker whom I hired, who had had a background of Reichian training was really most helpful to me. She helped me to learn that the most effective response, the most effective listening was where you listened for the feelings and emotions that were behind the words, that were just a little bit concealed, and where you could discern a pattern of feeling behind what was being said.

I think she’s the one who first suggested that the best response was to reflect these feelings to the client. Reflect is a word that later made me cringe. At the time, it really was very helpful to me in my work as a therapist. I was very grateful to her. I felt I learned a great deal from her and she learned very little from me.

Then I came to my transition to a full-time university position where, with the help of students, I was finally able to scrounge the equipment for recording our interviews, a dream I’d had for a number of years. I just can’t exaggerate the excitement of our learnings as we clustered about the machine, which enabled us to listen to ourselves playing over and over again some puzzling point in the interview at which something clearly went wrong, or focusing on those moments in which there seemed to be a response that helped toward significant forward movement in the interview.

I guess, I still regard listening to one’s recorded interviews as perhaps the very best mode of improving one’s self as a helping person. Among many lessons from listening to these recordings, we came to realize that listening to feelings and reflecting them was a vastly complex experience.

We discovered that we could pinpoint a therapist response where significant forward movement occurred. We could, where perhaps the client was talking in a vague and desultory fashion, and one therapist’s response would enable him to really begin to move. You could also pinpoint the responses for a nice forward-moving process that was brought to a dead stop by one particular response.

In such a context of learning, it became quite natural that we focused upon the content of the therapist’s response rather than upon the empathic quality of the listening, and no longer particularly apologized for that. It probably was a necessary step in our learning. To this extent, we became very much conscious of the techniques that the counselor or therapist was using.

We became really expert in analyzing in minute detail. I can remember sitting around with students and picking apart sentences and particular phrases and words. We profited a great deal from that very microscopic study of the interview process. I think we gained a great deal from it.

This tendency to focus on the therapist’s responses had consequences, which appalled me. I was meeting considerable hostility as to my point of view, and that really didn’t seem to bother me, but this kind of thing did bother me because the whole approach came in a few years to be known as a technique. Non-directive therapy, it was said, is the technique of reflecting the client’s feelings, period. Then you’ve taken care of non-directive therapy or even worse.

The even worse caricature was simply that in non-directive therapy, you just say the last say back the last words that the client said. Really, I was so shocked and appalled by that complete distortion of our approach that, for a number of years, I said almost nothing about the empathic listening. When I did, it was to stress an empathic attitude with very little comment as to how that attitude might be implemented in the relationship.

I just became frightened of the distortion. I preferred to discuss the qualities of positive regard and therapist congruence, which I’d come to hypothesize as being two other conditions that were growth-promoting in a relationship. Those concepts were often misunderstood too, but they never came to be caricatured in the same way that the empathic listening was caricatured.

Over the years, however, the research evidence keeps piling up and it points strongly to the conclusion that a high degree of empathy in a relationship is possibly the most potent factor. Certainly, one of the most potent factors in bringing about change and learning. I believe it’s time for me to forget the caricatures and misrepresentations of the past and take a fresh look at empathy.

For still another reason, it seems timely to do this. In the United States, during the past decade, many new approaches to therapy have held center stage; gestalt therapy, psychodrama, primal therapy, bioenergetics, rational emotive therapy, and transactional analysis are some of the best-known, but there are more, and part of their appeal seems to me to lie on the fact that, in most instances, the therapist is clearly the expert actively manipulating the situation often in dramatic ways for the client’s benefit.

If I read the science correctly, I believe that there is some decrease in the fascination with such expertise in guiding people. With another approach that is based on expertise, however, behavior therapy, I think there’s no doubt that the fascination with that approach is on the increase. I think I can really understand that. I think a technological society has been delighted to find a technology by which man’s behavior can be shaped, even without his knowledge or approval toward goals that the therapist chooses or that have been chosen by society. Yet even here, much questioning by thoughtful individuals is springing up as the philosophical and the political implications of such an approach become more clearly visible. I’ve seen a willingness on the part of many to take another look at ways of being with people which evoke self-directed change and locate power in the person, not in the therapist, and this brings me again to examine carefully what we mean by empathy and what we’ve come to know about it.

To formulate a current description, I would want to draw on the concept of experiencing as formulated by Eugene Gendlin. Briefly, it’s his view that, at all times, there is going on in the human organism a flow of experiencings to which the individual can turn again and again as a referent in order to discover the meaning of what he is experiencing.

He sees empathy as pointing sensitively to the felt meaning which the client is experiencing in this particular moment in order to help him focus on that meaning and to carry it further to its full and uninhibited experiencing. An example may make more clear both the concept and its relation to empathy. A man and an encounter group is making some vaguely negative statements about his father, and the facilitator says, “It sounds like you might be angry at your father.”

“No, don’t think so.” “Dissatisfied with him?” “Perhaps.” “Disappointed in him?” “Yes, that’s it. I am disappointed in him. I’ve been disappointed in him ever since I was a child because he is not a strong person.” I think that an example does illuminate Gendlin’s concept in this way: Against what is the man checking these various terms? Angry? No, that isn’t it? Dissatisfied? Well, that’s closer. Disappointed? Ah, that matches the flow of, I think, visceral experiencing that’s going on within.

A person has a very sure knowledge of that flow and can really tell when you’re speaking to it. In other words, the right word, the right label, or the right phrase often taps the exact meaning of the flow that is going on within him that he hasn’t been able to label or understand himself. It enables him to bring into awareness the real meaning of what’s going on within.

With that conceptual background, I’d like to attempt a description of empathy which would seem satisfactory to me today. I would no longer be terming it a state of empathy, which was in my earlier definition, because I believe it to be a process rather than a state, and perhaps I can capture that quality.

The way of being with another person, which is termed empathic, has several facets. It means entering the private perceptual world of the other, and becoming thoroughly at home in it. It involves being sensitive moment to moment to the changing felt meanings which flow in this other person, to the fear or rage or tenderness or confusion or whatever that he or she is experiencing.

It means temporarily living in his life, moving about in it delicately without making judgements, sensing meanings of which he is scarcely aware, but not trying to uncover feelings of which he is totally unaware since this would be too threatening. It includes communicating your sensings of his world, as you look with fresh and unsighted eyes at elements of which he is fearful.

It means frequently checking with him as to the accuracy of your sensings and being guided by his responses. You are a confident companion to him in his world. By pointing to the possible meanings in the flow of his or her experiencing, you help him to focus on this useful type of referent to experience his meanings more fully and to move forward in his or her experiencing.

Now, to be with another in this way means that, for the time being, you lay aside the views and values that you hold for yourself in order to enter his world without prejudice. In some sense, it means that you lay aside yourself, and this can only be done by a person who is secure enough in himself that he knows he will not get lost in what may turn out to be the strange or bizarre world of the other, and can comfortably return to his own world when he wishes.

Perhaps that description makes clear that being empathic is a complex, demanding, strong, yet subtle and gentle way of being.

I think now I’d like to move on to ask the question, what have we come to know about empathy through research? The answer is that we’ve learned a great deal. I’ll try to present some of these learnings giving first some of the general findings which were of interest to me, but I’m going to reserve, until the latter part, the analysis of the effects of an empathic client on the recipient because I think there’s a lot to be said about the effects that it has on the recipient.

Here then are some of the general statements which can be made with some assurance. I’m going to put them all as though they were knowledge quotes, but we all know that research knowledge is limited to the population which was studied, the various qualifications. All of those qualifications should be made in regard to each of the rather blunt statements that I’m going to make.

First of all, we know that the ideal therapist is, first of all, empathic. In a study of therapists to get them to formulate their concept of the ideal therapist, these were therapists from, I think, at least eight different orientations in therapy, empathy was placed in the very highest rank out of 12 possible variables, and the definition of empathy was similar that used in this paper. It corroborates a much earlier study by Fiedler done many years ago.

We may include that the thing that most therapists are trying to do, their highest priority, is to be empathic. Another statement I’ll make very briefly is that it’s been learned that a high degree of empathy in a relationship is associated with various aspects of process and movement in therapy. There is a clear correlation between the degree of empathy and the relationship and the measures of process or progress through therapy.

A finding which is exciting to me and I feel hasn’t been adequately exploited is that the degree of empathy which exists and which will exist in a relationship can be measured and determined very early in the game. In therapy interviews, it can be determined certainly by the fifth interview. A German research says it can be determined in the second interview, and that that’s very closely related to the success or lack of success in the total relationship.

To me, that’s an exciting finding because it means that perhaps we could save enormous amounts of time if we determined, by some objective measure, the empathic quality of a relationship early in the game, so that we would know whether it was at any high probability of success or not. If you find a highly empathic quality in a relationship, it is highly probable that the therapist is the one who is responsible for that.

One finding that is a little bit hopeful but also expected is that experienced therapists offer a higher degree of empathy than inexperienced, which is only to say that maybe over the years, therapists do come a little closer to being the ideal therapist they would like to be. Quite important finding is that the better integrated the therapist is within himself, the higher the degree of empathy that he exhibits. Personality disturbance, various kinds of adjustment problems, in the therapist, tend to be correlated with a lower degree of empathic quality in the relationships that he offers. As I’ve considered this evidence, and also my own experience in the training of therapists, I come to the somewhat uncomfortable conclusion that the more psychologically mature and integrated the therapist is as a person, the more helpful is the relationship he provides.

I’d say that’s kind of an uncomfortable conclusion because it really throws out a challenge to all of us who are in the helping professions. If we are no better as helpers than we are as people that’s– which it seems to me this is somewhat saying, that’s a sobering thought. Then another quite exciting and also sobering finding is from a study by Raskin.

Let me describe it briefly. He got interviews from six experienced therapists. If I name their names, you would recognize all of them. I don’t know if he’s going to publish the names, so I’m not going to name them here. From six different orientations. Each therapist selected an interview which he regarded as characteristic and typical of his own work and submitted it for this research purpose.

Raskin picked a large segment of each of those interviews to be rated by 83 therapists of eight different orientations, so that here was the actual therapeutic work of six experts being rated by a large number of mostly experienced therapists, some inexperienced, but mostly experienced therapists.

There are two findings. One is interesting. It is that the degree of empathic quality in those relationships varies enormously. For the statistically minded, it’s at a 0.001 level of significance, the difference in the degree of empathic quality. The other finding is that he correlated the ratings of the six expert therapists with the ideal therapist that had formerly been formed from the judgments of these 83 therapists. There, it is sobering. Two of these well-known therapists correlated positively with the ideal. Four correlated negatively, one at a -0.66.

That, in the paper, I’d say so much for therapy as it is practiced. It is a very sobering thing to think that possibly we are that far from what we would like to be as therapists. The next finding then is not surprising at all. It is that therapists are quite inaccurate in assessing the quality of their own relationships. I won’t go into the complicated reasoning, but there’s good evidence of both clients and unbiased raters are better judges of the empathic quality of the relationship than is the therapist himself. The practical implication would be that if we want to know whether we are understanding our clients, we should let them tell us.

What effects do a series of deeply empathic responses have upon the recipient? Here the evidence is quite overwhelming. From schizophrenic patients to pupils in ordinary classrooms, from clients of a counseling center to teachers in training, from neurotics in Germany to the neurotics in the United States, empathy is clearly related to positive outcome. There are just many studies that indicate that.

Bergin and Strupp summarize it by saying that various studies demonstrate a positive correlation between therapist empathy, patient self-exploration, and independent criteria of patient change so that you could say empathy and process and outcome are all positively related. I believe that we haven’t paid perhaps enough attention to that.

I want to discuss it more now from perhaps a clinical point of view. I was going to say subjective, maybe clinical would be a better term. What is the effect on the person who’s the recipient of a high degree of empathic listening? In the first place, it dissolves alienation. For the moment at least the recipient finds himself a connected part of the human race, though he may not articulate it clearly, his experience goes something like this:

“I’ve been talking about hidden things, partly veiled even for myself, feelings that are strange, possibly abnormal, feelings I’ve never communicated to another, not even clearly to myself, and yet he or she has understood them even more clearly than I do. If he knows what I’m talking about, what I mean, then to this degree, I’m not so strange or so alien or set apart. I make sense to another human being. I am in touch with, even in relationship with others. I am no longer an isolate.”

Perhaps that explains one of the major findings of our study of psychotherapy with schizophrenics. We found that those patients receiving, from their therapists, a high degree of accurate empathy as rated by unbiased judges, showed the sharpest reduction in schizophrenic pathology is measured by the MMPI. This suggests that sensitive understanding by another may have been the most potent element in bringing the schizophrenic out of his estrangement and into the world of relatedness.

Jung has said that the schizophrenic ceases to be schizophrenic when he meets someone by whom he feels understood. Our study provides empirical evidence in support of that statement.

Other studies, both of schizophrenics and of counseling centered clients show that low empathy is related to a slight worsening in adjustment or pathology. Here too, the findings make sense, I think, though it’s sobering sense to think that we may make people worse by not offering a high degree of empathy.

One of Ronald Laing’s patients states vividly his experience in earlier contacts with psychiatrists. He says it’s the most terrifying feeling to realize that the doctor can’t see the real you, that he can’t understand what you feel, and that he’s just going ahead with his own ideas. Beautiful description. Patient says, “I would start to feel that I was invisible or maybe not there at all.” I think that’s why it would have a worsening effect to feel, “If I’m not understood and he’s going off on his own track, maybe I’m horrible, maybe I’m so abnormal. Nobody can understand me.”

Another meaning of empathic understanding to the recipient is that someone values him, cares, accepts the person that he is. It might seem here that we’ve stopped talking about empathy and we’re talking about caring but that’s not quite so. It’s impossible, accurately, to sense the perceptual world of another person unless you see that, unless you value that person and his world, unless you, in some sense, care, hence the message comes through to the recipient that this other individual values me, thinks I’m worthwhile.

Perhaps I am worth something, perhaps I could value myself. Perhaps I could care for myself. I’d like to give a somewhat lengthy example of this from a young man who’s been a recipient of much sensitive understanding and who’s now in the latter stages of therapy. I’ve used this example before, but to me, it’s a gym that is worth repeating.

Client says, “I could even conceive of it as a possibility that I could have a kind of tender concern for me. Still, how could I be tender, be concerned for myself when they’re one in the same thing, but yet I can feel it so clearly, like taking care of a child, you want to give it this and give it that. I can kind of clearly see the purposes for somebody else, but I can never see them for myself that I could do this for me. Is it possible that I can really want to take care of myself and make that a major purpose of my life? That means I’d have to deal with the whole world is if I were the guardian of the most cherished and most wanted possession that this I was between this precious me that I wanted to take care of and the whole world. It’s almost as if I loved myself. That’s strange but it’s true.”

A therapist says, “It seems such a strange concept to realize it would mean I would face the world as though a part of my primary responsibility was taking care of this precious individual who is me, whom I love.”

Client goes on there, “Whom I care for, whom I feel so close to. That’s another strange one.” Therapist says, “It just seems weird.” Client, “Yes, it hits rather close somehow. The idea of my loving me and the taking care of me, that’s a very nice one, very nice.”

It is, I believe, the therapist’s caring understanding exhibited in this excerpt as well as previously which has permitted this client to experience a high regard, even a love, for himself. Still another impact of a sensitive understanding comes in its non-judgmental quality. The highest expression of empathy is accepting a non-judgmental. This is true because it’s impossible to be accurately perceptive of another’s inner world if you have formed an evaluative opinion of him.

If you doubt this statement, choose someone whom you know with whom you deeply disagree and who is in your judgment definitely wrong or mistaken. Now try to state his views, beliefs, feelings so accurately that he will agree that this is a sensitively correct description of his stance. If you’re like me, I think you’ll find that nine times out of ten you will be unable to do that if you feel judgmental toward this person, because your judgment of his views creeps into your perception and description of him.

Consequently, true empathy is always free of any evaluative or diagnostic quality. This comes across to the recipient with some surprise. “If I’m not being judged, perhaps I’m not so evil or abnormal as I’ve thought. Perhaps I don’t have to judge myself so harshly thus gradually the possibility of self-acceptance is increased.”

Perhaps another way of putting some of what I’ve been saying is that a finally tuned understanding by another individual gives a recipient his personhood, his identity. Laing has said that the sense of identity requires the existence of another by whom one is known. Buber has also spoken of the need to have our existence confirmed by another. Empathy gives that needed confirmation that one does exist as a separate valued person with an identity.

I think when a person’s selfhood or identity is pretty tentative or not very strong, I question whether he can achieve a real identity without someone understanding him. I do regard it as quite possible when he’s developed a strong selfhood really feels confidence in himself, then he might be able to affirm some new facet of himself without anyone else understanding it. At least that seems to me like a hypothetical possibility.

Yet, for myself, I guess it comes home to me mostly with new ideas. I can only affirm them tentatively until someone else has understood them, then they seem to become much more possible and I’m much more capable of affirming them then if they’ve proved really understandable to someone else. I don’t just mean intellectually understandable but really understandable at some gut level.

Let me turn to a more specific result of an interaction in which the individual feels understood. He finds himself revealing material. He has never communicated before and, in the process, he discovers a previously unknown element in himself. Such an element may be, “I never knew before that I was angry at my father,” or “I never realized that I’m afraid of succeeding.”

Such discoveries are unsettling but exciting. To perceive a new aspect of oneself is the first step toward changing the concept of oneself. The new element is in an understanding atmosphere owned and assimilated into a now altered self-concept. This is the basis, in my estimation, of the behavior changes which come about as a result of therapy or groups and so on.

Once the self-concept changes, behavior changes to match the freshly perceived self. Then if we think, however, that empathy is effective only in the one-to-one relationship that we call psychotherapy, we are greatly mistaken. Even in the classroom, it makes an important difference. When the teacher shows evidence that he or she understands the meaning of classroom experiences for the student, learning improved.

In a study made by Aspy, it was found that children’s reading improved significantly more when teachers exhibited a high degree of understanding and in classrooms which such understanding did not exist. To me, that’s not surprising. Just as the client in psychotherapy finds that empathy provides a climate for learning more of himself, so the student in the classroom finds himself in a climate for learning subject matter when he is in the presence of an understanding teacher.

Just recently, after I’d written this, I received a new manuscript by Aspy which summarizes almost a dozen years of work. Now covers several countries, thousands of pupils and teachers many, many classrooms. What I’ve said here is more than born out by the much further extended research. I had some copies of that with his permission run off and you’ll find those in the office, and those of you in education, I think, would be quite interested.

Again, not necessarily surprised is what we would like to believe is what we think when we try to be human in the classroom, but it’s the evidence that you can show to your board of trustees or to your principal or whatnot. It is evidence that being human, being understanding really pays in the classroom in many other ways in just learning subject matter too.

Thus far, I’ve spoken to the more obvious change-producing effects of empathy. I should like to turn to an aspect having to do with the dynamics of personality. I’ll make several brief statements and then endeavor to explain their meaning and significance. When a person is perceptively understood, he finds himself coming in touch with a wider range of his experiencing. This gives him an expanded referent to which he can turn for guidance in understanding himself and in directing his behavior.

If the empathy has been accurate and deep, he may also be able to unblock a flow of experiencing and permitted to run its uninhibited course. You may well ask me what do I mean by those statements? I believe they’ll be clear if I present an excerpt from a recorded interview with a woman in the later stages of therapy. This too is an excerpt I’ve used before but it’s particularly appropriate here.

A middle-aged woman is exploring some of the complex feelings that have been troubling her. She says, “I have the feeling it isn’t guilt.” She begins to weep. “Of course, I mean I can’t verbalize it yet. It’s just being terribly hurt.” The therapist says, “It isn’t guilt except in the sense of being very much wounded somehow.” She continues weeping. “Often I’ve been guilty of it myself, but in later years, when I’ve heard parents say to their children ‘Stop crying’ I’ve had a feeling, a hurt, as though, well why should they tell them to stop crying? They feel sorry for themselves, and who can feel more adequately sorry for himself than the child?” “Well, that’s what I mean, as though I thought that they should let him cry and feel sorry for him too maybe in a rather objective way. That’s something of the kind of thing I’ve been experiencing just right now.” The therapist says, “That catches a little more of the flavor of the feeling that it’s almost as if you’re really weeping for yourself.”

“Yes, and again, you see there’s conflict. Our culture is such that one doesn’t indulge in self-pity, but I feel it doesn’t quite have that connotation. May have.”

The therapist says, “You think there’s a cultural objection to feeling sorry about yourself and yet you feel the feeling you’re experiencing isn’t quite what the culture objects to either?”

“Then, of course, I’ve come to see and to feel that over this, see, I’ve covered it up,” and she bursts into tears, “But I’ve covered it up with so much bitterness, which in turn I had to cover up. That’s what I want to get rid of. I almost don’t care if I hurt.”

The therapist, “You feel it here at the basis of it as you experience it is a feeling of real tears for yourself, but that you can’t show, you mustn’t show. That’s been covered by bitterness that you don’t like, that you’d like to be rid of. You almost feel you’d rather absorb the hurt than the feel of bitterness, and what you seem to be saying quite strongly is, ‘I do hurt and I’ve tried to cover it up.'”

Client says, “I didn’t know it.” The therapist says, “Like a new discovery really.” The client, “I never really did know, but it’s almost a physical thing. It’s as though I were looking within myself at all kinds of nerve endings and bits of things that have been mashed.” Therapist says, “As though some of the most delicate aspects of you physically almost have been crushed or hurt.” She says, “Yes. I do get the feeling, ‘Oh, you poor thing.'”

Now here, I think, it’s clear that empathic therapist responses encourage her in the wider exploration of, and closer acquaintance with, the visceral experiencing that’s going on within. She’s learning to listen to her guts, to use that in elegant term. She has expanded her knowledge of the flow of experiencing within herself. Here too, we see again how this un-verbalized visceral flow is used as a reference.

How does she know that guilt is not the word to describe her feeling? By turning within, taking another look at this reality, this palpable process, which is taking place, this experiencing.

I think, in the example I was giving, that it’s pretty clear that when a person is perceptively understood and he comes, in this case, she, comes in touch with a wider range of her experiencing is able to use that more as an expanded reference and is able, and this is, I think, a concept that’s a little difficult to catch, is able to let a blocked experiencing carry itself through to its real conclusion.

Now, I’m coming to the conclusions that I want to make in regard to the paper. Really two concluding sections. I want now to back off and give a rather different perspective on the significance of empathy. We can say that when a person finds himself sensitively and accurately understood, he develops a set of growth-promoting or therapeutic attitudes toward himself.

Let me explain what I mean. First of all, the non-evaluative and acceptant quality of the empathic climate enables him, as we’ve seen, to take a prizing, caring, even loving attitude toward himself. Second, being listened to by an understanding person makes it possible for him to listen more accurately to himself with greater empathy toward his own visceral experiencing, his own vaguely-felt meanings, but his greater understanding and prizing of himself opens up to him new facets of his experience, which become a part of a more accurately based self.

His self is now more congruent with his experiencing. Thus, he has become, in his attitudes, toward himself, more caring and acceptant, more empathic and understanding, more real and congruent, but these three elements are the very ones which both experience and research indicate are the attitudes of an effective therapist.

We are perhaps not overstating the total picture if we say that an empathic understanding by another has enabled the person to become a more effective growth enhancer, a more effective therapist for himself. Consequently, whether we are functioning as therapists, as encounter group facilitators, as teachers, or as parents, we have in our hands, if we’re able to take an empathic stance, a powerful force for change and growth. I think its strength needs to be appreciated.

Then finally, I want to put all that I’ve said into a larger context. Because I’ve been speaking only of the empathic process, it may seem that I regard it as the only important factor in growthful relationships. I would not wish to leave that impression. I’d like briefly to state my views as to the significance of what I see as the three attitudinal elements making for growth in their relationship to one another.

In the ordinary interactions of life between sex partners, between teacher and student, employer and employee, or between colleagues, it’s probable that congruence is the most important element. Such genuineness involves letting the other person know where you are emotionally. It may involve confrontation and the owned and straightforward expression of both positive and negative feelings.

Thus congruence is a basis for living together in a climate of realness. In certain other special situations, caring or prizing may turn out to be the most significant. Such situations include nonverbal relationships, parent and infant, therapist and mute psychotic, and the like. Caring is an also an attitude which is known to foster creativity, a nurturing climate in which delicate and tentative new thoughts and productive processes can emerge.

Then, in my experience, there are other situations in which the empathic way of being is the highest priority. When the other person is hurting, confused, troubled, anxious, alienated, terrified, when he is doubtful of his own self-worth, uncertain as to his identity, the gentle and sensitive companionship of an empathic stance, accompanied, of course, by the other two attitudinal elements, provides illumination and healing. In such situations, it is, I believe, the most precious gift that one can give to another.”

A full video of the talk can be found here.